Gerbert d'Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures

In the year 967 C.E., a young man left his home in the Benedictine monastery of Aurillac, France, and headed south to the Spanish March, a region wedged between two tenth-century superpowers – one Christian, one Muslim. His host and traveling companion was Borell, the Count of Barcelona, and this journey was the beginning of a remarkable three-year sojourn in an equally remarkable region – a sojourn that launched the young man’s career as an important scholar and churchman. The young man was named Gerbert, and the mathematics he learned in the blend of cultures that was medieval Catalonia gave him an advantage that led to power and fame in his lifetime and to notoriety and legend in the centuries to come.

Gerbert d'Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures - Introduction

In the year 967 C.E., a young man left his home in the Benedictine monastery of Aurillac, France, and headed south to the Spanish March, a region wedged between two tenth-century superpowers – one Christian, one Muslim. His host and traveling companion was Borell, the Count of Barcelona, and this journey was the beginning of a remarkable three-year sojourn in an equally remarkable region – a sojourn that launched the young man’s career as an important scholar and churchman. The young man was named Gerbert, and the mathematics he learned in the blend of cultures that was medieval Catalonia gave him an advantage that led to power and fame in his lifetime and to notoriety and legend in the centuries to come.

Gerbert d'Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures - The Spanish March

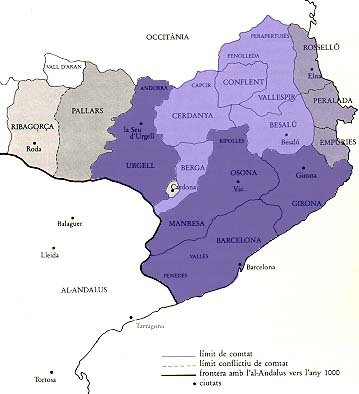

In Charlemagne’s empire, frontier regions, especially those between Christian and non-Christian territories, were called marches; that’s where we get the term marquis. One of those border regions, the March of Spain (later called Catalonia), maintained its identity and autonomy long after the death of Charlemagne. Organized as a Christian frontier against the Muslims, and situated between the much larger and more powerful Christian Frankish kingdoms to the north and the Muslim Caliphate of Cordoba to the south and west [see the map], it necessarily developed ways to coexist with widely varying societies.

In fact, the region itself had a long history of cultural blending resulting from its conquest and occupation by many peoples over the years. If we look at a map of the area in the year 900 C.E., we see the region, labeled County of Barcelona, as part of the West Frankish Kingdom. In the year 700, it was ruled by the Visigoths. Before that, it was part of the Roman Empire. And of course there were native peoples there before the Roman armies arrived. So the medieval Catalan culture was an amalgamation of native, Roman, Visigoth and Frankish backgrounds.

During the Middle Ages, the Counts of Barcelona maintained cultural, economic and political ties with Rome as well as with the South of France and Muslim Spain. The regions exchanged ambassadors, merchants, goods, customs – and knowledge, including mathematics. While the rest of Western Europe slumbered in its “Dark Ages,” Catalonia flourished because of its proximity to the lively center of knowledge in Cordoba and the merchants arriving from the East on its Mediterranean shores. In fact, Greco-Arabic science and mathematics were introduced into Western Europe via Catalonia.

Gerbert d'Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures - Gerbert d'Aurillac

Gerbert was born around the year 945, probably near the French town of Aurillac. At a young age, he was taken to the nearby monastery, where he lived and studied for a career in the church. The abbot there was a learned and courageous man, who made certain that his pupils studied the “pagan” classics as well as the required religious texts. And so young Gerbert learned Greek and Latin, and to love Plato and Vergil as well as the works of the early church fathers.

In the year 967, Count Borell of Barcelona visited the monastery on retreat. When he left, the abbot asked him if there were men in Spain versed in the [liberal] arts. When Borell assured him that the Spanish March sheltered several monasteries with vast libraries and many active scholar-monks, the abbot asked the count if he would take the young Gerbert back to Catalonia with him, as he had exhausted the scholarly resources of Aurillac. Borell agreed, and Gerbert’s new life began.

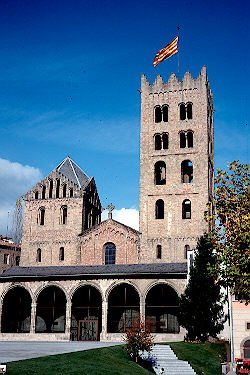

Gerbert’s official biographer, his student Richer of Rheims, tells us that Gerbert studied in the monastery at Vich. But modern scholars agree that, to learn the things he did, he must have spent some time at the fabulous monastery at Ripoll.

The abbey of Santa Maria de Ripoll, high in the mountains of northeastern Spain, was the jewel of Catalonia. It was established as a center of religious and intellectual life in the 9th century by Count Wilfred the Hairy, the acknowledged founder of Catalonia, and its library was legendary. It contained many liturgical books, including beautiful examples of calligraphy, Visigothic texts (one from the 9th century describes how to compute the date of Easter) and Mozarabic documents, including Arabic translations of Boethius’ Arithmetica. During the 10th century, at the time when Gerbert would have visited Ripoll, the monks there were translating Arabic works into Latin. And so the young Gerbert did indeed have access to many wondrous new ideas. Richer reports that when Gerbert was taken to meet Pope John XIII and, later, the Holy Roman Emperor Otto I, they were astonished at his knowledge of science and mathematics.

The Abbey of Santa Maria de Ripoli

Gerbert d'Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures - The Surprising Mathematics of Gerbert

Gerbert was proficient in two subjects that may well have impressed and astonished an emperor and a pope – the use of an astrolabe, and calculating with Hindu-Arabic numerals. Both topics, as we shall see, were well-known to Eastern scholars in the tenth century, and were transmitted to the West through the monasteries of Spain.

The astrolabe was an astronomical device widely-known in the East; its use was described in several documents of the time. One of those documents, the Sententiae Astrolabii,was translated in the tenth century from Arabic into Latin by an obscure scholar named Lupitus of Barcelona. It has been suggested that the original manuscript was in fact the work of the great al-Khwarizmi. At any rate, we know that there was a copy of it in the scriptorium of the monastery at Ripoll during the years when Gerbert was there.

Gerbert described, in his Geometria, how to use an astrolabe to find the altitude of a triangle – a use far from its intended astronomical uses. Later, when he was appointed the head of the cathedral school at Rheims, he taught young men training for the church, and used pedagogical devices such as the astrolabe, the monochord, and hand-made models of spheres to teach mathematics and its relation to music and astronomy.

The Cathedral at Rheims

Gerbert d'Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures - Hindu-Arabic Numerals

Gerbert also described a new system of representing numbers – a system very familiar to us today, but unknown in Western Europe at the time, where Roman numerals were still the order of the day. The new numerals, called ghobar (“dust,” from writing the numerals in the dust of a counting board) or, more generally, Hindu-Arabic, consisted of nine symbols, plus (later) a zero. Any number could be represented by placing the symbols next to each other in a particular order. The shape and orientation of the numerals evolved over the years, but at the time of Gerbert they looked something like this:

These numerals had been known in India since the sixth century C.E., and in the eighth century they began to be transmitted to Arabic scholars, who discovered how to represent decimal fractions, as well as whole numbers, with them. It wasn’t long before Arabic works describing the new system of numeration were translated into Latin; the earliest known is The Book of Addition and Subtraction according to the Hindu Calculation, by Muhammed ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi (c. 780–850). Al-Khwarizmi is probably the most famous Eastern mathematician known to students of mathematics in the West. His name gave us the term algorithm, and the word algebra first appeared in his writings. His treatise about “the Hindu calculation,” written about 820, was almost certainly available in the Spain of the tenth century.

Other scholars whose works would have been accessible to Gerbert were Abu al-Rayhan al-Biruni (973 – 1048), also from Central Asia, and Abu Sahl al-Kuhi, who lived in the second half of 10th century in Tabaristan (Persia).

There were also Jewish scholars living and working in the courts of the caliphs. Abu Sahl Dunas ibn Tamim was active in Kairouan (Tunisia) in the tenth century. Writing in Arabic in a commentary in the year 955, he mentioned an earlier work in which he described the use of Hindu numerals.

Gerbert d'Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures - Gerbert's Abacus

Gerbert devised a new kind of abacus which one could use to calculate with the Hindu numerals, a flat board with columns drawn on it, corresponding to ones, tens, hundreds, and so forth. (Some scholars believe he may have been the first person to use the Latin term abacus.) He had a shield-maker construct small pieces of animal horn with the numerals on them; called apices, the pieces could then be placed on the board to represent numbers. A zero was not necessary; the absence of a marker in the tens’ place, for instance, meant that there were no tens. An eleventh-century manuscript found in Limoges illustrates the representation of numbers on such an abacus. (Note that the numerals had changed slightly in the next hundred years.)

Gerbert compiled a list of rules for computing with his abacus, Regula de Abaco Computi, in which he painstakingly explained how to multiply and divide, as well as add and subtract, in the new system. A companion work, Liber Abaci, by his student Bernelin, is often included in the collected works of Gerbert; it predates the book of the same name by Fibonacci by two hundred years.

To see an example of how to add numbers using Gerbert’s abacus, download the PowerPoint file, Adding Two Numbers on Gerbert's Abacus.

And for an example of subtraction, download the PowerPoint file, Subtracting with Gerbert's Abacus.

Gerbert d'Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures - Gerbert's Legacy

We have seen that Gerbert was truly a man in the right place at the right time: his study in the Spanish March in the tenth century introduced him to mathematical ideas from Latin, Arabic, Indian, and Jewish scholars. He was instrumental in introducing Hindu-Arabic numerals to Western Europe. He taught a generation of students about the astrolabe and the abacus. His knowledge was so surprising, so new and different, that some people accused him of obtaining it through supernatural, or even demonic, means. William of Malmesbury, writing one hundred years later, calmly stated that Gerbert studied astrology with the Arabs and learned magical arts from them. Some of the more colorful legends that grew up about Gerbert were that he could fly, that he had a mistress who was a witch, that he constructed a huge talking head who gave him the answers to mathematics problems. Even today, his tomb is reputed to weep upon the death of a pope.

Despite his notoriety, Gerbert was elected Bishop of Rome in the year 999; the name he chose as pope, Sylvester II, honors the first Sylvester, who – according to legend – baptized Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor. And so even Gerbert’s choice of a papal name combined Christian and pagan legacies.

Gerbert’s home town of Aurillac now proudly claims him as a native son. There is a statue of him in that city, honoring the young man who left his humble home to travel to a new land, where he learned mathematics so strange and wonderful that it brought him to the attention of the most powerful men in Europe – until finally he became one of them.

Gerbert d'Aurillac and the March of Spain: A Convergence of Cultures - Bibliography

Berggren, L., Episodes in the Mathematics of Medieval Islam, New York: Springer, 1986.

Bernelin, Élève de Gerbert d’Aurillac, Libre d’abaque: réalisé après le manuscrit du XIème siècle, Pau: Princi Néguer, 1999.

Hill, G.F., The Development of Arabic Numerals in Europe, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1915.

Kunitzsch, P., The Arabs and the Stars: Texts and Traditions on the Fixed Stars and their Influence in Medieval Europe, Northampton: Variorum Reprints, 1989.

Kūshyār ibn Labbān, Principles of Hindu Reckoning, transl. by M. Levy and M. Petruck, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965.

Lattin, H.P., Letters of Gerbert, New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.

Lewis, A.R., The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718-1050, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1965.

Mann, V. B., Dodds, J. D. and Glick, T. F., eds. Convivencia: Jews, Muslims, and Christians in Medieval Spain, New York: The Jewish Museum, 1992.

Menocal, M.R., The Ornament of the World: How Muslims, Jews and Christians Created a Culture of Tolerance in Medieval Spain, Boston, New York and London: Little, Brown and Co., 2002.

Millàs Vallicrosa, J., Assaig d’Història de les Idees Físiques i Matemàtiques a la Catalunya Medieval, Barcelona: Edicions Científiques Catalanes, 1983. [Reproduction of 1931 original.]

Riché, P., Gerbert d’Aurillac, le Pape de l’An Mil, Paris, Fayard, 1987.

Richer, Histoire de son Temps, transl. by J. Guadet, Paris: Jules Renouard, 1845.

Roth, N., Jews, Visigoths and Muslims in Medieval Spain: Cooperation and Conflict, Leiden, New York and Köln: E.J. Brill, 1994.

Sylvester II, Oeuvres de Gerbert, Pape sous le Nom de Sylvester II, transl. by A. Olleris, Clermont: F. Thibaud, 1867.