- About MAA

- Membership

- MAA Publications

- Periodicals

- Blogs

- MAA Book Series

- MAA Press (an imprint of the AMS)

- MAA Notes

- MAA Reviews

- Mathematical Communication

- Information for Libraries

- Author Resources

- Advertise with MAA

- Meetings

- Competitions

- Programs

- Communities

- MAA Sections

- SIGMAA

- MAA Connect

- Students

- MAA Awards

- Awards Booklets

- Writing Awards

- Teaching Awards

- Service Awards

- Research Awards

- Lecture Awards

- Putnam Competition Individual and Team Winners

- D. E. Shaw Group AMC 8 Awards & Certificates

- Maryam Mirzakhani AMC 10 A Awards & Certificates

- Two Sigma AMC 10 B Awards & Certificates

- Jane Street AMC 12 A Awards & Certificates

- Akamai AMC 12 B Awards & Certificates

- High School Teachers

- News

You are here

The Wrong Door, Or Why Math Gets a Bad Rap

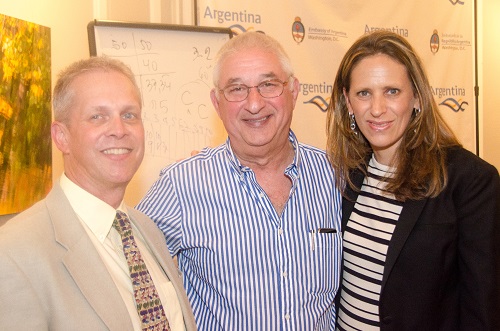

Mathematician Adrián Paenza (center) with the ambassador of Argentina, Cecilia Nahón and the executive director of MAA, Dr. Michael Pearson.

Imagine, says Adrián Paenza, someone who has never heard a piece of music. Not Beethoven. Not the Beatles. Not so much as “Happy Birthday.”

Now suppose you have the privilege of initiating this person into music appreciation. What would you play? Vivaldi? Madonna? Eminem, perhaps?

The possibilities abound, of course, but Paenza quickly eliminates some of them: “You wouldn’t start with a military march, right?”

Paenza believes that introducing students to mathematics by drilling them on arithmetic facts is comparable to beginning someone’s exposure to music with the likes of “Yankee Doodle.”

Or take this homier analogy: “You wouldn’t invite someone over to your house and say, ‘Okay, right here: This is the bathroom.’ But that’s what we do. We show students the wrong side.”

Or “The Wrong Door,” as Paenza titled the talk he gave at the Embassy of Argentina in Washington, D.C., on July 7 in an event cosponsored by the MAA and the Georgetown University Center for Latin American Studies.

An Argentine mathematics professor and journalist, Paenza received the International Mathematical Union’s prestigious Leelavati Prize in August 2014 in recognition of his contributions to changing the public perception of mathematics. Paenza hosts two weekly television shows, and his children’s book series, Matemática . . . ¿estás ahí? or Math . . . Are You There?, has popularized mathematics throughout Latin America and Europe. (See Paenza’s full Leelavati Prize citation at http://bit.ly/1q8iXKG.)

Questions They Didn’t Ask

“Assume I came here and told you how to collect stamps from Thailand,” Paenza said to his embassy audience. “How long would you stay?”

Most listeners would stick around for a few minutes out of politeness, Paenza predicted, but would then begin to drift away, uninterested.

Event attendees don’t want to listen to the answers to questions they didn’t ask, after all. And neither do students.

So here’s what happens (in Paenza’s words) when kids are compelled to endure the unmotivated mathematics force-fed them at school:

They go home and they speak with their father and mother and say, “Let me ask you: When am I going to use this?” And their mother and father, they don’t know either because they didn’t know when they were taught that. So what do they answer? “You’ll see later.” But when does “later” arrive? People have been waiting and waiting for that “later” to come and it never comes.

They Don’t Know What It Is

Misconceptions about mathematics are widespread, Paenza noted. Ask a passerby what a mathematician does, and you’re more likely to hear speculation about speedy completion of long calculations than an accurate explication of mathematical proof.

Paenza told a story about an unwed princess courted by all the eligible bachelors in her father’s kingdom. They formed a queue at the palace on an appointed day, and each in turn attempted to impress the royal daughter. An acrobat, a bodybuilder, a magician—each strutted his stuff. But the princess remained unmoved.

Finally the throng of contenders had dwindled to one, a short man wearing a backpack. This unassuming beau removed from his backpack a pair of eyeglasses and handed them to the princess. She put them on and smiled at her future husband.

“The problem is not that she didn’t appreciate,” Paenza stressed. “She didn’t see. People reject something that they don’t know. People reject mathematics only because they don’t know what it is.”

We Have to Share the Knowledge

Paenza had a man from a pizza shop—call him José—on his television show once. To illustrate a point he was making, Paenza wanted José to cut a pie in a nonstandard way. In describing the orientation and relative position of the desired cuts, Paenza used the word “perpendicular.”

José froze.

Paenza rephrased using “90 degrees.” Still nothing.

Telling José to “make a cross” finally got the job done, but the interaction made Paenza ponder the power dynamic at play when there’s a knowledge imbalance between two people.

“Knowledge is power, and, when you know something, you have power over the other person,” Paenza said on July 7. “You own him or her at least in that particular circumstance. You have something that he doesn’t.”

And it’s not fair.

“If you know something, you have to share it,” Paenza said. “We have to socialize the knowledge.”

Where the Weird Things Are

So if you know mathematics, don’t keep it to yourself.

Let the uninitiated in on your process. Show them the intermediate steps by which you reach your final answer. Entice your audience with the subject’s playful side. Admit that you make mistakes.

If a student asks whether you’ve committed the 15 times table to memory (this happened to Paenza), sit down (as he did), and help him or her work it out.

Encourage a pair to exchange encrypted messages and try to decode them.

Derive the counterintuitive result that, as long as there are 23 people, there’s a more than 50 percent probability that two of them share a birthday. Test this in a crowded room.

Tell kids about game theory.

“Show them where the weird things are,” Paenza entreated. “Challenge them because we are challenged.”

Written by Katharine Merow

News Date:

Monday, August 17, 2015

Category: